“I’m not against peace

Peace is against me

It wants to eliminate me

Erase my heritage.”

—from “Meen Erhabe” (Who’s the Terrorist by DAM)

Teach for Palestine is the name of the website where I discovered the kind of text I was looking for. Four months into the most documented genocide in history and I was still figuring out how to include the discussion on the longstanding Palestinian struggle in my lessons. Schools, or at least my classes just couldn’t go on business as usual, as if we don’t live in a most tumultuous time when moral choices—and pedagogical decisions—are put to a test. Just like how I have started spotlighting climate texts since the 2020 pandemic, I actively sought for texts on Palestine that I could use in class and stumbled upon the melodically titled 2008 documentary by Palestinian filmmaker Jacqueline Reem Salloum. Edited from 700 hours’ worth of footage gathered for almost five years by the filmmaker and her subjects, Slingshot Hip Hop is highly acclaimed for its raw yet hopeful presentation of the Palestinian spirit through the lives of rappers who use music as a form of protest against Zionist occupation.

Before the screening, I called one student to act out the words in the title for the rest of the class to guess. It had taken a bit of time before anyone guessed the first word as slingshots are no longer as abundant as they used to be, at least not anymore in the lives of middle-class youth. Hip hop, when acted out as a term, also had not been easy for it encapsulates an entire subculture expressed through music, fashion, and swag. After the charade, I asked the students to mull over the words and the narratives they carry— “slingshot” and “hip hop.” There was a sharing about the popular story of David and Goliath, about how the former, the obvious underdog, defeated the latter, an impossible enemy, using a rather unsophisticated weapon that is the slingshot. Building upon the insight, I added the significance not to mention the iconicity of the slingshot to the Palestinian struggle. Because what else could anyone living in a place surrounded with rubble do to defend themselves other than to assemble a weapon made out of what can easily be found among piles of debris such as wood, rubber, and stones? Slingshot couldn’t help but become the ingenious defense of the oppressed. I also asked the students to go back to the popular history of hip hop, about its being a creative expression popularized by the Latinos and African-Americans, marginal communities living amidst the culture of white supremacy. Juxtaposed, “slingshot” and “hip hop” presents a complementary binary—the material and the cultural, the urgent and the long-term.

This could be a good take off to more meaningful conversations until anyone who would also like to teach the film finds themselves in a place where one has to tread lightly. In a context where peace education is popularly defined, accepted, and taught as “a continuing process of education focusing on a body of shared values, attitudes, behaviors, and ways of life based on non-violence” (Mabunga, 2016), how could one address the question of, to begin with, what having to use a slingshot stand for? How could one differentiate for students between just resistance and terrorism when governments and institutions that officialize labels deliberately conflate the two? Slingshot Hip Hop reminds its viewers that the contexts of material conditions and history are imperative for an accurate understanding of the existence of social movements across the world.

Half of the documentary consists of scenes depicting the Palestinian plight—limited to lack of basic resources for decent living; mechanisms to restrict mobility such as Apartheid walls, checkpoints, and curfew; Arabophobia; censorship, arbitrary shootings and arrests, among others. Oppressed nations are no strangers to this treatment. In the Philippines then and now, farmers remain at the mercy of landlords; workers with their meager salary could barely keep up with rising costs of living; indigenous peoples are driven away from their ancestral lands for large-scale projects that destroy ecosystems; dissenters are surveilled, censored, faced with trumped-up charges, and / or disappeared. These conditions are, in the first place, the primary determinants of radicalization among colonized peoples, whom out of self-preservation are pushed to forming resistance groups. Much like the Katipuneros, Huks, and present-day heroes of the continuing Philippine Revolution, Palestinian freedom fighters prove the steadfastness of the colonized spirit, the necessity and inevitability of fighting back despite the extensive invalidation machinery of imperialist logic.

Yet, Slingshot Hip Hop is about hip hop as much as it is about slingshot. In the scene where DAM, a Palestinian rap group, visits a youth center, a child asks if he is a Palestinian. DAM answers, “Yes, you’re Palestinian. What do you think you are?” “An Arab,” the child answers. Having lost their parents to prison or death, the children could no longer go to school even if only to learn their own identity. Concerned groups like DAM visit them every now and then, would also go so far as set up clubs that gather children and engage them in fun activities in the hopes of winning them over to the side of music, lest they lose them to the bleak yet accessible future in drug dealing. In Palestine, teaching children how to rap is giving them tools to tell their story. Like the slingshot made out of materials found in debris, rapping is making music out of nothing but one’s voice.

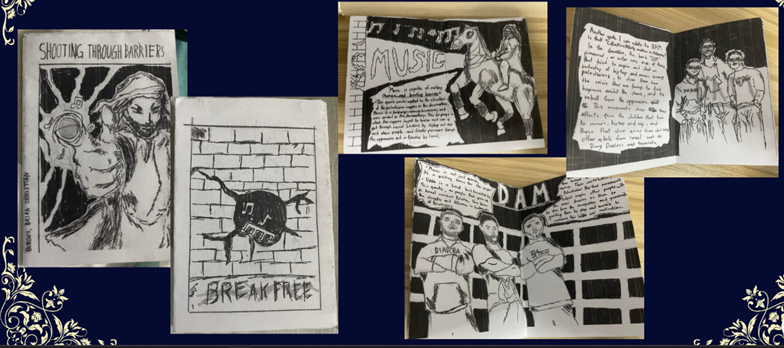

Films like Slingshot Hip Hop is a way to harness the strength of art to shape critical consciousness in class. After the screening and our discussions about it, I requested the students to try sharing their own struggles through rap. For review of poetic rhythm, I showed a Filipina-produced rap sample and encouraged them to go back to the scene where DAM and friends of a martyred young man were trying to write a rap song for his tribute. The students’ rap pieces centered on students’ woes, inflation, gentrification, gender-based marginalization, overseas Filipino workers, among other topical issues at the time. We also made zines reflecting poetic and visual responses to the documentary. “But you need to do more than perform,” says DAM in an interview. The strength of Slingshot Hip Hop as a text to teach peace could be seen not only in its illustration of the power of art, but more importantly in its admission of art’s limitations. While it has the capacity to describe the roots of resistance, art does not address them. Artists well-knowledgeable of this reflexivity would have their art lead the audience to more tangible expressions of dissent. Protests, boycotts, and encampments of the #FreePalestine movement are getting stronger by the day. Wanting to learn more about and eventually practicing them would be a remarkable indicator of a grounded appreciation of peace education.

(In time for the United Nations declaration of the International Day of Peace, Roma Estrada writes about peace education through film about Palestine’s resistance against Israel’s attacks.)

israel, palestine, peace, Slingshot Hip Hop